Report From Houston

Houston-based artist Laura Napier was in the midst of writing a second installment of her "Report from Houston" for Settlers + Nomads this summer when forecasts of Hurricane Harvey broke. After the devastating storm, she added an introduction to her photo essay on pump jack art, reporting on the impact of Hurricane Harvey on Houston artists and nearby refineries and chemical plants (Napier's artistic research focuses on the social cultures of the oil and gas industries of Texas). Hurricanes Irma and Maria followed Harvey with a vengeance, and our heartfelt thoughts are with all those so tragically impacted by recent disasters. Houston's recovery efforts are slow and ongoing. Thanks, Laura, for sharing this link:Wondering how to help with Harvey recovery from afar? Consider supporting frontline communities (marginalized populations who live closest to chemical plants and are the most vulnerable). https://anothergulf.com/a-just-harvey-recovery/

by Laura Napier

Downstream

Greetings from Houston, Texas. I began writing this post before the arrival of Hurricane Harvey on the Gulf Coast. My studio is at ground level in the hundred-year floodplain, so to prepare I moved tools and art upstairs, and elevated anything else above three feet. I moved my partner Justin’s van to the second floor of a parking garage. Because everything is vulnerable in a hurricane and flood prone region, my digital archives are backed up in cloud storage, and my physical art archives are stored in the second story of Box 13 ArtSpace, a fortress like cement building on high ground on Harrisburg Boulevard. We thought about, but didn’t leave Houston before the storm hit, because we felt the places we could evacuate to were just as imperiled. Mont Belvieu, where Justin’s mom lives, is too close to petrochemical plants and storage facilities, and our friends at Habitable Spaces in Kingsbury would be subject to high winds and flooding. We did not have funds to check into a hotel further north. We knew that we wouldn’t be able to leave just before the storm, because the roads would be clogged with evacuees, and later, highways would be underwater.

We used our stored water and ate out of cans for a few days, although we didn’t need to get out the camp stove. I cleared the storm drains on the corner every morning. Floodwater backed up our driveway but never made it into the studio. Not everyone was so lucky. Several Houston artists whose studios flooded began circulating crowdfunding campaigns, exceeding their monetary goals within hours of posting. Justin and I went to help move artwork, archives, and cameras to safety at the flood damaged home of one such artist, photographer and friend Keliy Anderson-Staley. As the storm subsided, leaders at Houston arts organizations began laying groundwork for the Harvey Arts RecoveryFund, in order to support individual artists and smaller arts organizations impacted by the storm.

Harvey also damaged refineries and chemical plants in the region. Refineries and petrochemical plants flared excess materials during shutdown, spilled chemicals, and are releasing more toxins during startup.(1) The East Harris County Manufacturers Association maintains the

CAER line

t

o alert surrounding communities of events and emergencies at their industrial plants. Corporate participation is voluntary. I check it every day. These days I also check the air quality index at

t

o help decide whether I should go outside or not, or even whether to leave the AC on. While the AQI only displays ozone and particulate matter readings online, to me the daily animated map loop visually correlates with daily releases of petrochemicals as plants are brought back online. To see how much dangerous industry is in the region, see the Sierra Club’s

map of major industrial sites that pose risk from Harvey damage.

Containers at the Arkema plant, twenty miles away in Crosby, began exploding early in the morning on August 31. (2) By that evening a group, including myself, figured out on the Facebook feed of

Bryan Parras

of

(Texas Environmental Justice Advocacy Services) that it smelled like “barbecue” in places miles apart, in Humble, and on the East Side, Midtown/Montrose, and Third Ward neighborhoods of Houston. The smell could easily have come from some other chemical release, no one knows for sure.

Media coverage during the storm drove people I know, isolated in their homes while sheltering in place, into mental anxiety. To keep healthy while we waited out the storm, Justin and I unplugged to play board games, called friends and family, and went on bike rides in the soaking rain to check on exhibition spaces at DiverseWorks and theBlaffer.

No bus today, Brays Bayou at Ardmore St and N MacGregor Way, Houston, August 27, 2017. Photo: Laura Napier

At Brays Bayou we watched a driver deliberately road rage their car into floodwaters, and stall out. The irony is not lost on me. If we don't stop using our carbon emitting, climate change causing cars, nature will take them away.

Upstream

Water in the Gulf is very warm this year, and that extra heat energy strengthens storms into strong hurricanes. More hurricanes per year are linked to climate change (3), and climate change is linked to oil. Which leads to Sea of Oil, my ongoing project exploring the social culture and impact of oil, gas, and the petrochemical industries on workers, families, and communities.

Watermelon Boy, George Kalesik, parking lot next to Dollar General, Luling, Texas. Photo: Laura Napier

This summer I revisited Luling in central Texas. Their biggest annual event is the Watermelon Thump, an opportunity for the town to elect a high school watermelon queen, sell watermelon pyramids at roadside stands, and stage a watermelon seed spitting contest. But what really put Luling on the map was oil, first found in 1922. Luling today still has small antique operating pump jacks dispersed all over town -- alongside houses, behind the dollar store, at the end of the driveway of the Dairy Queen, in the city park, in the parking lot of the local bank. Sixteen are now disguised as art. Made by a self-taught sign painter named George Kalesik, who lives in another small town nearby, the work was commissioned and is celebrated by the Luling Area Chamber of Commerce.

Oil in Texas has been an amusement for a long time. There's an old 1901 photo of the original Lucas gusher at Spindletop, showing oil shooting diagonally away from a wooden drilling rig into a black inky blot suspended in the sky. Looking carefully at the photograph, one notices people are wearing their Sunday best. On the right are instruments – a drum, a trombone, and a band of musicians facing the crowd. In the back left of the photograph people line the edge of a dirt berm, presumably the edge of an open pit that the oil is raining down into. The image is inscribed on the lower right with the photographer’s name, Trost. In German trost means comfort, or consolation. Nowadays, here they call the smell of oil the smell of money.

Spindletop, Texas, 1901. Photographer: Trost Studio

In reality smells from the jacks in Luling are the smell of poison. Sour crude contains hydrogen sulfide. Oil wells leak the gas, which when inhaled, is highly toxic to the central nervous system and acts a lot like carbon monoxide. There are 184 wells dispersed throughout Luling, according to the Luling Area Chamber of Commerce.

I am inviting you to look at these jacks as virtual art tourists, but know that we are looking at dangerous industry dressed up as fun. You know the story about Las Vegas, that tourists would watch nuclear tests out in the desert from rooftops. Tourism makes technologies that can lead to mass extinction (nuclear annihilation, massive global warming) seem tame through entertainment.

Angler in a Boat, George Kalesik, surrounded by residences. Photo: Laura Napier

Girl Picking Flowers, George Kalesik. Photo: Laura Napier

Eagle, George Kalesik, Blanche Square Park, Luling. Photo: Laura Napier

Thirsty bird (slang for pump jack) next to a sport field and playground in public park. These art jacks appeal to children. This protective fence is low and flimsy.

See Saw Kids, George Kalesik, in front of Elgi Rubber. Photo: Laura Napier

DQ Dude, George Kalesik, next to drive through line at Dairy Queen. Photo: Laura Napier

Luling Eagle Quarterback, George Kalesik. Photo: Laura Napier

You may have noticed that these idyllic images of leisure feature only idealized white, working class cartoon characters. While one hears a lot about historic German immigration to central Texas, there were slaves in Caldwell County, and later, black sharecroppers picking cotton in Luling and nearby. Mexican Americans also have strong heritage here, the land used to be part of Mexico. The indigenous were there before everyone else. All have been erased from these visual representations.

Grasshopper, George Kalesik, in backyard. Photo: Laura Napier

Grasshopper is another slang term for a pump jack. There were toys in a yard to the right of this photograph.

Surfing Flamingo in Car, George Kalesik. Photo: Laura Napier

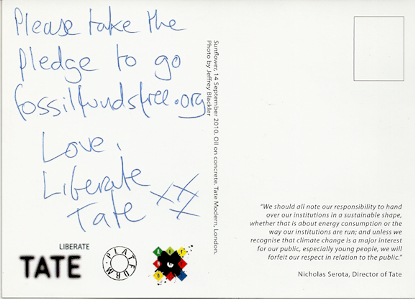

This is art literally propped up and moved by and cloaking oil. A metaphor for how the art world is funded here in Houston. Last October, members of the activist artist collective Liberate Tate gave a talk at Art League Houston outlining their activist performances in London, and hosted a workshop centered on oil in Houston the next day at Alabama Songwith collective exercises, mapping, and breakout sessions. They encouraged all artists in the room to sign a pledge not to show art funded by oil (see fossilfundsfree.org.I wasn’t sure what to do. Every art organization in Houston, the universities, parks, almost everything is propped up by oil corporation money. To sign would mean to refuse to work or exhibit in Houston, or alternatively, to gain a problematic reputation by sending strongly worded letters to the boards of every art nonprofit, college, and university I work for or show with.

“Please take the pledge to go fossilfundsfree.org Love, Liberate Tate XXX”, Liberate Tate, scan of postcard distributed at Alabama Song, 2016

Or artists could just go with the flow, pretend that everything is still okay, make more metaphorical art pump jacks. “Have a good time, everybody!” Trump said when visiting an area evacuee shelter, “It’s been really nice. It’s been a wonderful thing. I think, even for the country to watch it and for the world to watch. It’s been beautiful.” (4)

Enjoy the show.

Click here to view Luling Pump Jacks by Laura Napier on vimeo.

LAURA NAPIER is a Houston-based artist and independent curator currently working in Houston on an artistic research project about the social cultures of the oil and gas industries of Texas. Her work explores behavior, sociology, and place through documentation, installation, and participatory and collaborative performance.

Title image: safety in action, Arkema, Crosby, Texas, September 24, 2017. Photo: Laura Napier

[1] “AT LEAST 10 HOUSTON AREA CHEMICAL FACILITIES AND OIL AND GAS REFINERIES HAVE ALREADY REPORTED PROBLEMS WITH DOZENS MORE THREATENED”, Sierra Club press release,

http://content.sierraclub.org/press-releases/2017/08/least-10-houston-area-chemical-facilities-and-oil-and-gas-refineries-have, accessed 9/3/2017

[2] “Explosions and Smoke Reported at Arkema Inc. Crosby Plant”, Arkema Americas corporate website statement,http://www.arkema-americas.com/en/media/news-overview/news/Explosions-and-Smoke-Reported-at-Arkema-Inc.-Crosby-Plant/, accessed 9/3/2017

[3] Jason Samenow, “Gulf of Mexico waters are freakishly warm, which could mean explosive springtime storms”, Washington Post, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/capital-weather-gang/wp/2017/03/22/gulf-of-mexico-waters-are-freakishly-warm-which-could-mean-explosive-springtime-storms/?utm_term=.cb069d7aa2a9, accessed 9/3/2017

[4] Rory Carroll, Julian Borger, “Trump visits Houston to meet Harvey Survivors: ‘Things are working out well’”, The Guardian,https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/sep/02/donald-trump-to-visit-houston-to-meet-storm-harvey-survivors, accessed 9/3/2017