LASSO OF TRUTH: WHY WE NEED WONDER WOMAN NOW MORE THAN EVER

By Danielle Kelly, originally published in the June 1 issue of the Las Vegas Weekly, Las Vegas, Nevada. The best Wonder Woman costumes didn’t require much. Some ’70s kids like myself had a rope that doubled as a golden lasso of truth, spinning in circles until it tumbled to the ground. Others, like Chelsea Cain, painted boots red and wore them every day until they no longer fit.

Cain, best-selling novelist and 2017 Eisner Award nominee for her work on the lightning-rod comic series Mockingbird, absorbed knowledge of Wonder Woman mostly “through word of mouth on the playground,” she says. “She was this mythological figure whose story was passed down from the older kids to the younger kids. I learned to play Wonder Woman at recess, years before I’d actually read a comic or saw the show.”

Wonder Woman, Charlie’s Angels, The Bionic Woman: the mid-’70s trifecta of smart, powerful and hyper-sexualized female television icons. Depending on your age, these women might still linger among your earliest memories. For a generation immersed in television like none before it, stealing secret, grown-up glimpses of the Angels fighting crime left a deep impression.

Lynda Carter as Wonder Woman. Photo: AP images

On the surface, that impression included some variation of “be sexy.” But don’t believe Wonder Woman was defined by her patriotic, if skimpy, costume. Even kids who didn’t see the TV show—and weren’t equipped to parse out the implications of her generous curves—knew her from magazine covers and Halloween costumes, Super Friends and Underoos. The hunger for heroes who happened to be female was more important than what they happened to wear. Young, impressionable girls and women just wanted to be inspired by someone kickass who looked like them. Or like someone they could be. They still do.

Trapped as we are in this polarized mess of an ideological and political web called 2017, women have emerged as central figures on both sides of the aisle. Popular culture is a litmus test of who we are and what we care about, while also preparing us for potential forks in the road. All things “woman” are in focus, and more politicized than ever; to use, attack, empower, troll, celebrate or generally market your message around women is de rigueur, and for good reason. Women who do heroic things are actually getting recognized for it.

We’re in the midst of immense change and chaos, and marching into that maelstrom comes the first major motion picture solely dedicated to the most famous female superhero of all time: Wonder Woman. But does a scantily clad, 75-year-old Amazonian still matter? In a world of Malala Yousafzais and Little Miss Flints, do little girls care about a superhero called Wonder Woman? And do they really need to?

Wonder Woman’s original purpose was distinct and remains so, setting her apart from other superheroes. In 1941, psychologist William Moulton Marston introduced a feminine alternative into DC’s hyper-masculine new comic universe. In his book Wonder Woman Unbound: The Curious History of the World’s Most Famous Heroine, author Tim Hanley describes Marston as a feminist who believed women were superior to men, more compassionate and emotionally intelligent, and thus physiologically predetermined to make better leaders.

Still from Dara Birnbaum’s Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman, 1978. Image from folksonomy.co

For Marston, women were poised to take over the world and create a more harmonious society, and the feminist Amazonian utopia depicted in the comic—and its famous ambassador—would help prepare society for that shift. Problematically, this utopian strength was derived from a hierarchical culture of submission, which in Marston’s eyes empowered women. Men needed to submit to the “loving authority” of women, metaphorically represented in Wonder Woman’s bondage-esque lasso and golden deflecting bracelets. (Jill Lepore’s The Secret History of Wonder Woman also famously details Marston’s kinky side and his heroine’s BDSM tendencies, dismantling his suspect brand of feminism.)

Fetishized and bound or not, Wonder Woman unmistakably represented feminist principles, intended to groom young people into strong, compassionate, informed adults, equipped to navigate the coming matriarchy. It was pretty radical for a man in 1941. It still is.

Early Wonder Woman comics felt revolutionary. Hanley notes that the series’ original associate editor was a woman, Alice Marble, who also contributed a “Wonder Women of History” feature, bringing young readers the stories of real-life heroines like Florence Nightingale. Hanley spotlights Wonder Woman’s drive to seek an alternative to physical violence and her dedication to worker’s rights and social justice. She gave up a perfect society to make our world a better place, forever shaped by the values of her Amazonian roots.

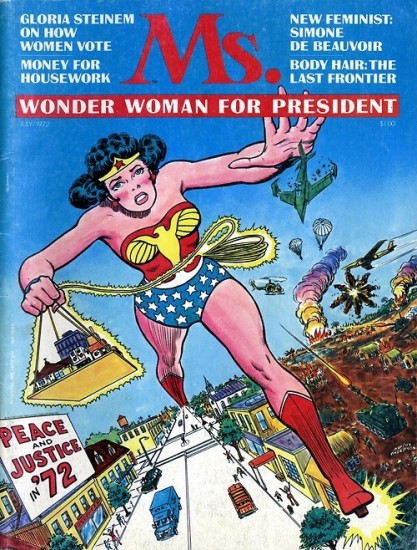

As with any fictional character, Wonder Woman’s core directives were at times compromised by the whims of contemporary culture. Hanley describes a late’-60s/early-’70s incarnation as a violent crime fighter with no superpowers but lots of cute outfits. In 1972, she was reclaimed by second-wave feminism with a Ms. magazine cover, and a compilation with an introduction written by Gloria Steinem.

Wonder Woman on the cover of Ms. magazine’s inaugural issue, 1972. Image via msmagazine.com

Three years later came the relatively simplistic Wonder Woman TV show, still superhero-y, but more invisible plane camp than real social justice, with enough revealing costumes to drive the most sex-positive second-waver bananas.

“Even when the feminism was trumpeted boldly … it could be pretty tone deaf,” Portland-based film critic and comics aficionado Marc Mohan tells the Weekly. “I think her feminist-icon status is to some degree by default, since she’s easily the longest-lasting, most prominent female comic book superhero ever, and because of that, she absorbs and reflects back the attitude of society at large.”

For Greg Rucka, societal trends and popular icons synchronized to perfection. An Eisner award winner and author of what many consider the definitive series of Wonder Woman stories in the mid-2000s, Rucka picked the story up again in 2016 and seized the contemporary moment as an opportunity to address, with little fanfare, Wonder Woman’s bisexuality. “To anyone who knows the character—who knows her as more than a hyper-sexualized pin-up, at least—[her sexuality] was self-evident,” Rucka says in an interview with the Weekly. “And it cannot ever be understated how important the acknowledgment of this core truth is to readers who are looking to see themselves represented in pop culture and who have, for years, been unable to find that representation.”

The most accurate depictions of Wonder Woman are those most loyal to her core tenets. When writing for Wonder Woman, Rucka used them as his guide. “Her capacity for empathy is enormous, and one that truly separates her from her peers.” She turns to aggression only as a last resort. “Violence is never her first option,” Rucka says.

For marriage and family therapist Christina Cay, this messaging is significant. “If we are surrounding girls with messages of women as powerful/brave/wise, these are the attributes we will believe women should have.” The same goes for the positive depictions of LGBTQ characters, and for the implications of depicting them at all. But adults need to help young minds process meaning. “When a parent watches a movie with their kiddo and says, ‘Well, the hero saved the day again,’ there is so much missed out on.” A character like Wonder Woman can create a rare opportunity for a parent to help a child work through an alternative example of heroism—sitting down to say, “Gosh, I admire Wonder Woman so much because while she won the day, she did it in a way that helped teach the villain the importance of peace and love in the world. That,” Cay suggests, “is true strength.”

The original Wonder Woman costume worn by Lynda Carter, part of the Incredible Costumes exhibit at the Children’s Museum of Indianapolis.

As with Cain’s red boots, it’s impossible to overemphasize the significance of play. Cay notes that, “Cartoon superheroes are more widely accessible and reach more countries and culture,” so the potential for impact is broad. With a fictional character comes the opportunity to “perform” behaviors. Children learn through play, using imagination to role-play scenarios, and experiment with meaning in real time.

Californian Michelle Reilly, mother to 3-year-old Averie, stresses that Wonder Woman “gives me something to strive for. I have an idea of how to be a strong mother and raise a strong female, [but] that idea is simplified and reinforced by my own image of strong women. … [Wonder Woman] is strength and broke the rules, and that’s what I want as a woman, for myself and my daughter.”

Part of Wonder Woman’s legacy is a set of feminine ideals at odds with prescribed gender roles, turning perceived disadvantages into strengths. Maybe a Wonder Woman has helped us recognize the Malalas of the world. And then there’s the F word. A minefield to be sure, but it remains an undeniable fact that, whether by default or successful design, Wonder Woman is a feminist icon, regardless of what she’s wearing.

“She was absolutely a feminist role model,” Cain stresses. “Wonder Woman is never defined by her womanhood. She’s a hero, just as much as Batman or Superman. She shows up, she saves the day. She’s not a ‘lady hero.’ She’s a superhero—a hero who happens to be female, not the other way around.”

Gal Gadot as Wonder Woman in the new 2017 film. Photo: Warner Bros

That status carries with it high expectations, so the new film will carry some heavy weight on its shoulders, to prove the merit of investing in a female superhero. “It’s not right,” Mohan says, “but if the upcoming movie tanks at the box office, it may be a while before we see a Marvel or DC big-budget film with a female lead.

“On the other hand,” he continues, “if it’s a terrible movie but does great business, we’ll probably see more terrible superhero movies with female leads. It’s as much a function of the industry’s sexism as it is Hollywood’s slavish avoidance of risk or originality.”

An ill-advised, recent cross-promotion pairing the film with diet bars reflects Hollywood’s outdated thinking on female-led movies. It also implies that Wonder Woman’s work is far from done. Asking whether she still matters tells us more about ourselves than it does about her. Why do we still have to ask the question at all? A justice-seeking, egalitarian, powerful, compassionate hero should never go out of style.

Perhaps 75 years of Wonder Woman has had an effect, inching us closer to Marston’s utopia. Vegas-based mother of four Ashanti McGee has a comic-reading teenage daughter who isn’t so into Wonder Woman, yet gravitates toward the queer-leaning, female heroines emerging in contemporary comics. McGee’s young son, however, loves Wonder Woman. And, “living in a world where boys can love Wonder Woman as much as any other superhero,” McGee says, “might just be what our little girls need.”

Danielle Kelly is a former Las Vegas resident and an artist and writer now based in Las Vegas, New Mexico. Kelly’s project-based practice ranges from installation to performance and has been featured in solo and group exhibitions in Los Angeles, Seattle, Las Vegas, San Francisco, and Portland,OR. Kelly’s writing has appeared in a variety of publications regionally including Las Vegas Weekly and Desert Companion. She currently serves as Executive Director for Surface Design Association.