Sean Slattery, The First 100 Days

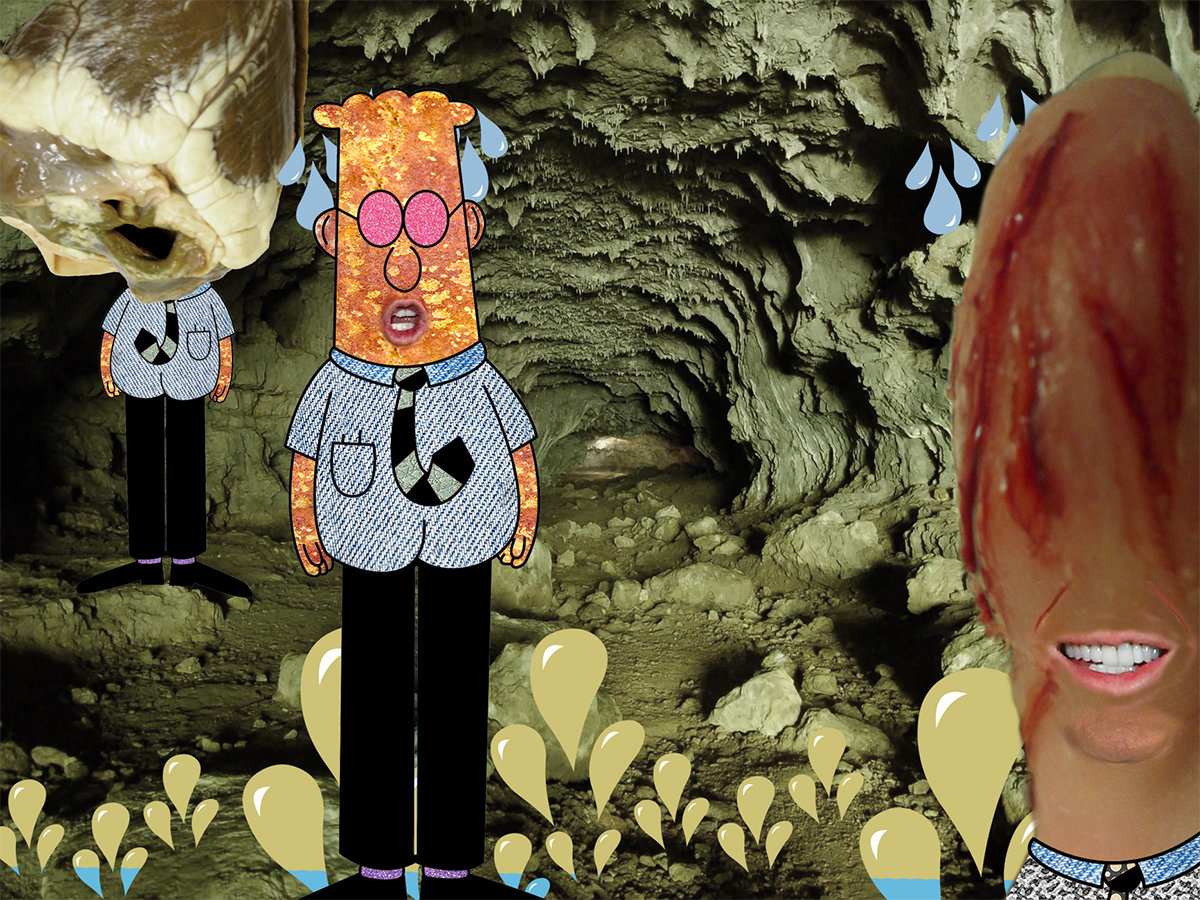

Sean Slattery, The Cave, pigment ink on paper, 2017

Sean Slattery, The First 100 Days

February 28, 2018 - March 30, 2018. Winchester Cultural Center Gallery

By D.K. Sole, July, 2018

In the early days of the current American presidency I remember people joking that at least the satirists and artists would have something to work with now. Sean Slattery's response to that challenge last March was, as far as I know, unique. Rebarbative, it went against the trend, in that it was obscure, elusive, baggy, and large, rather than clear, satirical, outraged, and immediate. That assertion of independence made me immediately cheerful. Even the premise seemed slippery. The artist promised to look at the presidency through the medium of Scott Adams' comic strip Dilbert – were we supposed to take him seriously or not? Adams is a Trump supporter, but still … Should we laugh?

(And you remember that every laugh at Dilbert is a prisoner's laugh.)

Sean Slattery, Familiar, digital print

Like Slattery's other work this exhibition was haunted by the unresolved magic of sources. What does it mean to choose a source? What does it mean to use it? What traces does it leave? While The First 100 Days was up you could have travelled twenty minutes down Maryland Parkway and seen the same questions asked by the pixelated edges of the cat and puppet pictures in his Familiar collage of 2015 at the Barrick's Plural show. Balancing that representation against The First 100 Days I felt as if I had seen him look up from the personalised unease of the Familiar and realise that a strong anxiety was gathering in the culture around him. "What," I imagined him asking himself, "is that anxiety made of?" And answers clustered in on him until a straightforward show became impossible. It was going to have the appearance of something groping about. The sources in Days lost the anonymity of the cat and Punch pictures in Familiar, but they didn't need it. The work knew – more confidently now – that it could generate its obscurities internally.

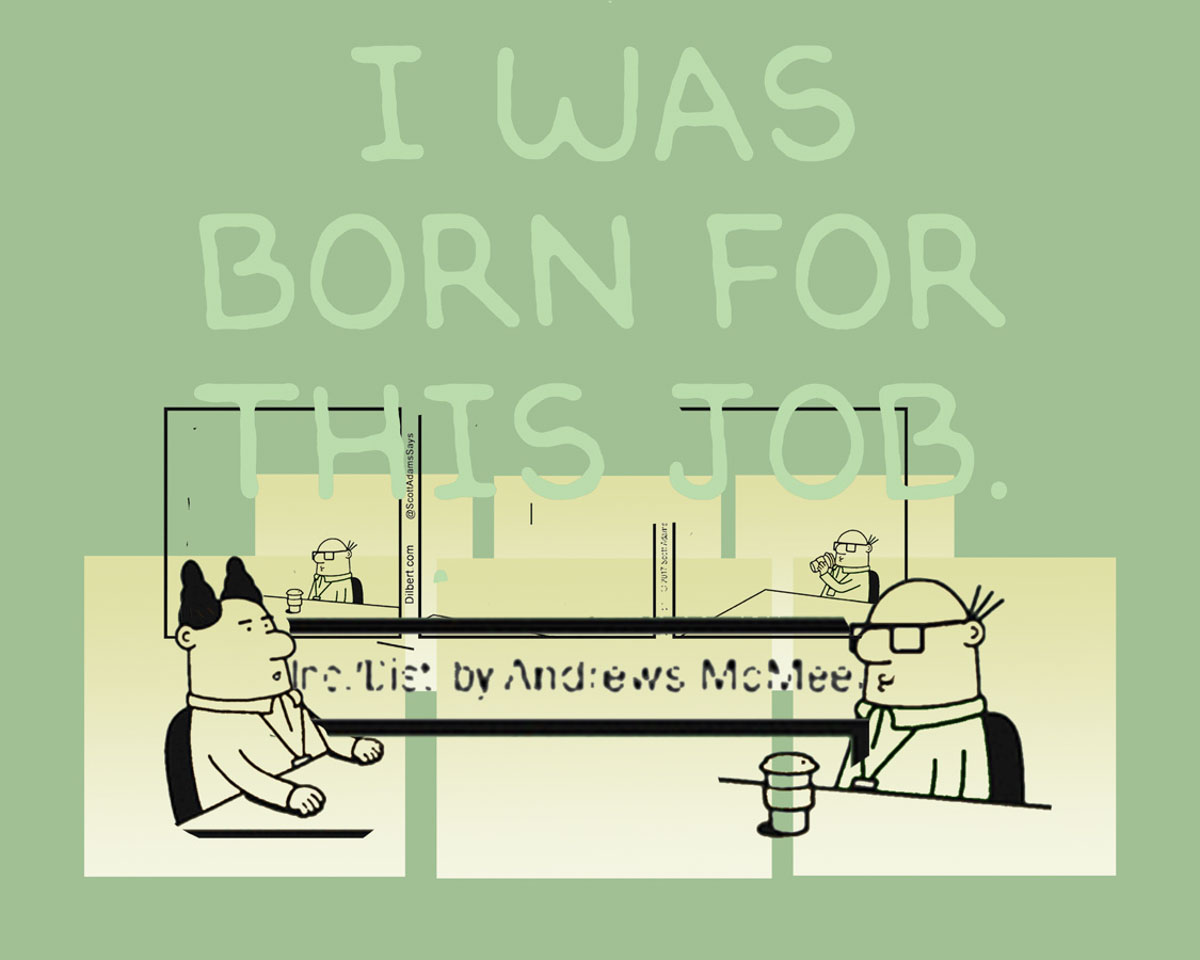

The Clark County website still has a page of text explaining the exhibition. It mentions Dilbert's role as an avatar of capitalist hopelessness. The text clarified a video component in Slattery's largest artwork, a rectangle of redrawn Adams strips that turned most of the gallery's only uninterrupted flat wall into a field of pale detail. The videos popped up on your phone when you scanned QR codes on some of the strips and you saw the artist reading the characters' dialogue out loud and commenting like a fan who had just encountered it that morning. His zeal was earnest enough to be suspect -- "You can see beyond the three panels of the comic and out into the big panel of your life!" he said in his commentary for the Dilbert from the 24th of April, 2017, three months after the inauguration – but if this was mockery then what was being mocked? As the artist's collaborator, his viewer, how could you join in?

Sean Slattery, detail, 86 Pencil Drawings for Dilbert by Scott Adams, graphite on paper, 2017-18

The website tells you that this fan gets angrier as you follow him chronologically from strip to strip. But I came at the rectangle before I read the website, and picked strips at random from the wall instead of looking for an order. Nothing seemed obviously wrong but I felt disconcerted. What had the artist done? What was going on?

The answer to that (which involved the punchlines in the strips being swapped out with lines from Jim Davis' Garfield*) pointed to a cycle of overwhelming misdirection that made this the key wall in the show. The website's assertion that, "The true Dilbert fan will immediately recognize challenges when they realize the punchlines are false," perpetuates the edge of mockery in the video. Surely even Adams himself would struggle to remember the punchline for the script he published on April 24th, when Slattery's doctored version, which replaces the words "That's the vibe I'm getting too" with "You sir, are a genius at understatement," doesn't sound out of character or change the meaning of the joke? Assuming that there were at least one hundred QR-coded strips on the wall (I didn't count them and with this show who should you trust?) it would have taken a dauntingly long time to clarify all of the falsifications. It struck me that this was a perfect historical portrait of the administration. There it is, the winning party, eating up a large space. But how weird it is, in spite of its obviousness, what strange and stupid lies it tells. What a miasma it creates in front of any investigation.

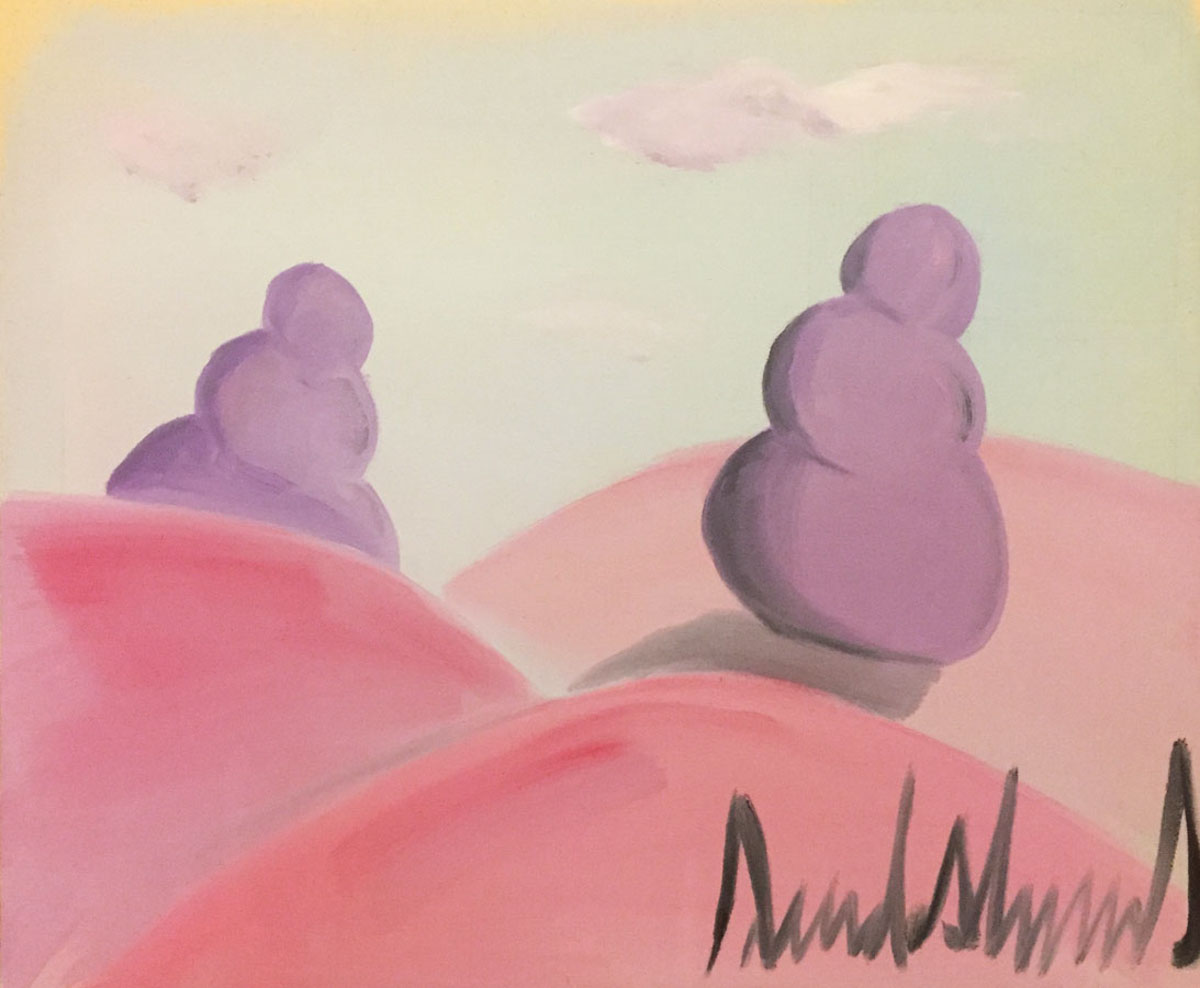

In context, the collages of animation cels and comic strip pictures on the adjacent wall could have been read as another comment on the act of falsification, since both animated cartoons and comic strip panels produce the illusion of movement without moving -- and if the Retired Trump/Retired Bush paintings opposite them -- mattress landscapes wearing clumps of Dilbert hair pretending to be trees -- can be partly understood as a commentary on the social framing of painting as an activity rehabilitatory, harmless, and "expressive" then do the collages also point to the illusion of movement in paintings everywhere, calling it out as a lie – or is this going too far?

The exhibition suggested some huge space of knowledge and refused to fill it, or, in the case of a digital collage of weird Dilbert figures with grafted body parts superimposed over a dark cave, hinted at an entire alternative show in a completely different style. That grim-coloured thing sat in the room of blues and baby-bedroom pastels like a moment of instinctive wilfulness on the part of the artist and suggested one reason why his work depicted the obfuscating shiftiness of the current White House so well. Like it, he behaved as if he had something to hide.

Sean Slattery, Dog Whistle, Pigment ink on paper, animation cel from Dilbert, tape, 2018

A piece of protest art like Indecline's naked The Emperor has No Balls creates a moment of concrete proof and reveals it to you totally, saying, "That's done, remember it: now, action!" The action promised by 100 Days was the slow procedure of unravelling or deducing. The show did not guarantee an easy time or even a pleasant time: the process would be boring and it would seem redundant. The source of unease is not singular. Where is it? Can we ever really find it? Will we be released at the end? This reading is not the one described on the website.

*I'm indebted to Dawn-Michelle Baude's review in the Las Vegas Weekly for this insight.

https://lasvegasweekly.com/ae/2018/mar/22/sean-slatterys-art-borrows-from-dilbert/

Australian artist D.K. Sole lives in Las Vegas, Nevada, and works at the UNLV Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art where she is in charge of Research and Educational Engagement. She has exhibited in Las Vegas and Denver, Colorado.

Las Vegas-based artist Sean Slattery makes work in digital and analog media. His work was most recently exhibited in Plural, Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art, UNLV; Tilting the Basin: Contemporary Art of Nevada, Nevada Museum of Art, Reno/downtown Las Vegas; and the Donna Beam Fine Art Gallery at UNLV.

All images courtesy Sean Slattery.